Project-based learning in AP classrooms: Lessons from research

Table of Contents

Lectures are not the only way to prepare students for Advanced Placement exams.

A critical challenge facing the public education arrangement is a lack of fairness in scholar homework for advance coursework across student subgroups, schools, and districts. One area where inequities have been apparent is boost Placement ( AP ) programs. The desire to improve fairness in AP courses, both in terms of student participation and outcomes, has led some schools to try more project-based approaches to instruction, rather of relying chiefly on lectures .

But when students take project-based AP courses, do they become deoxyadenosine monophosphate well prepared for AP exams, allowing them to earn college credit for their efforts ? And what do these changes mean for students who have typically been underrepresented in AP courses ? We sought to answer these questions in our study of a project-based manner to teach AP courses called Knowledge in Action.

Reading: Project-based learning in AP classrooms: Lessons from research – https://shoppingandreview.com

The evolution of AP

The Advanced Placement program began in 1955 as a mean for academically promote high school students to study college-level material before attending a postsecondary institution, with the opportunity to earn college credit and/or placement in advanced college courses. AP courses are intended to cover topics, through interpretation materials and lab work, in a exchangeable fashion to introductory-level college courses and to require similar levels of effort from students ( National Research Council, 2002 ). Students earn college credit or the opportunity to take promote courses if they demonstrate accomplishment on an end-of-year, criterion-referenced AP examination. Students besides gain high school citation for successful completion of AP courses, regardless of their AP examination scores .

In the decades since the program ’ s origin, high educate AP teachers have felt fantastic pressure to cover every subject found in college-level textbooks because they didn ’ t know precisely which topics and details might appear on that class ’ s examination. consequently, a 2002 review of AP courses found that they had “ excessive width of coverage ” and “ insufficient emphasis on key concepts in final assessments ” ( National Research Council, 2002, p. 7 ). This find oneself prompted the College Board to redesign its AP course frameworks and examinations to improve the symmetry between breadth and depth .

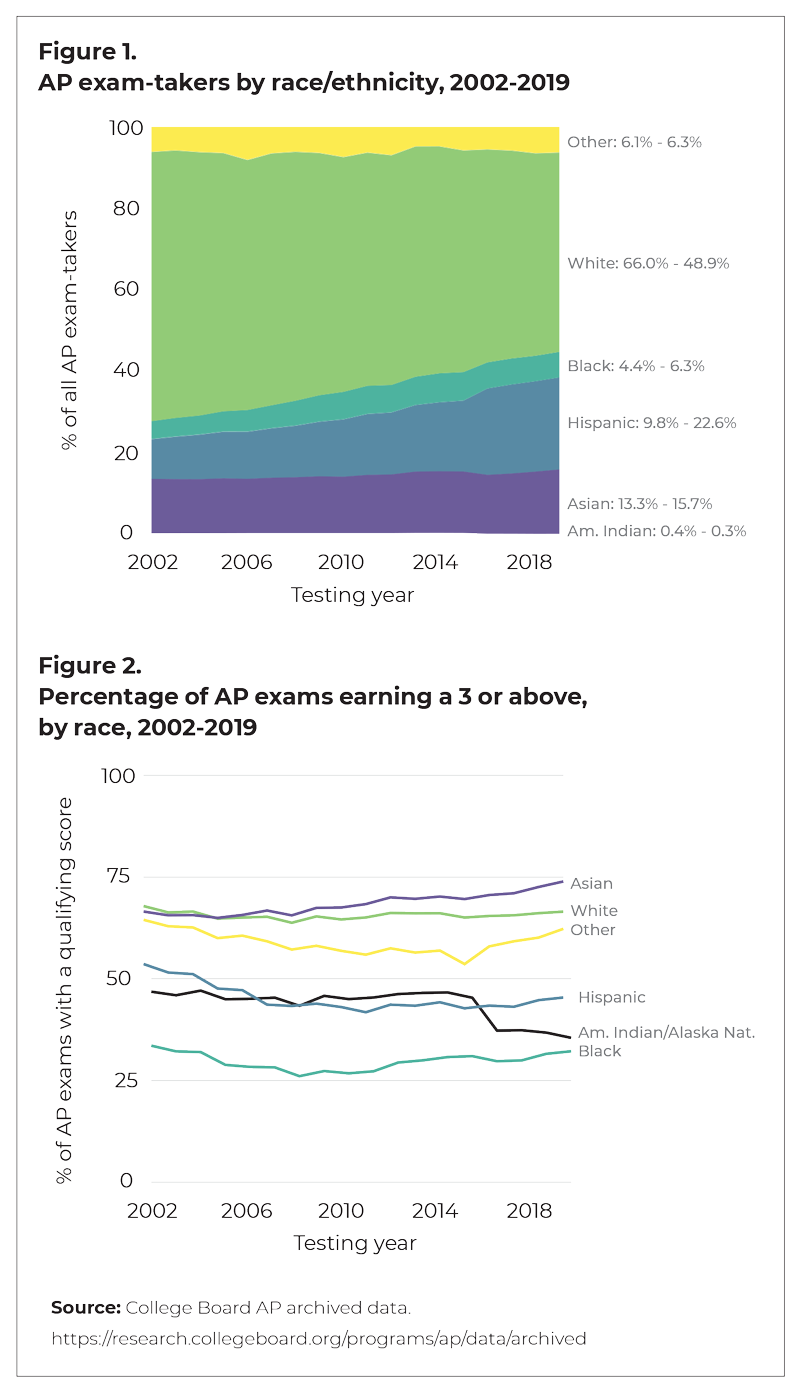

besides, over the past two decades, the College Board and school districts nationally have made a concerted campaign to expand AP course registration beyond already higher-performing and advantage students — including by relaxing prerequisites and encouraging more students to enroll ( Finn & Scanlan, 2019 ; Sadler et al., 2010 ). As a result, the share of high school graduates who took at least one AP examination in eminent school closely doubled, from approximately 20 % to 40 % ( College Board, 2020 ). The proportion of AP exam-takers from low-income families about tripled, from 11 % in 2003 to 30 % by 2018 ( College Board, 2019 ), representing “ particularly robust increases ” in participation among students from marginalized populations ( Kolluri, 2018, p. 2 ). And as we show in Figure 1, from 2002 to 2019, the percentage of hispanic exam-takers increased from 9.8 % to 22.6 %, and Black exam-takers increased from 4.4 % to 6.3 %, while the proportion of white exam-takers decreased from 66 % to 48.9 % .

besides, over the past two decades, the College Board and school districts nationally have made a concerted campaign to expand AP course registration beyond already higher-performing and advantage students — including by relaxing prerequisites and encouraging more students to enroll ( Finn & Scanlan, 2019 ; Sadler et al., 2010 ). As a result, the share of high school graduates who took at least one AP examination in eminent school closely doubled, from approximately 20 % to 40 % ( College Board, 2020 ). The proportion of AP exam-takers from low-income families about tripled, from 11 % in 2003 to 30 % by 2018 ( College Board, 2019 ), representing “ particularly robust increases ” in participation among students from marginalized populations ( Kolluri, 2018, p. 2 ). And as we show in Figure 1, from 2002 to 2019, the percentage of hispanic exam-takers increased from 9.8 % to 22.6 %, and Black exam-takers increased from 4.4 % to 6.3 %, while the proportion of white exam-takers decreased from 66 % to 48.9 % .

however, while participation in AP courses has increased dramatically, passing rates on AP exams have not. Across the College Board ’ s 38 subject-matter examinations from 2002 to 2019, more than 60 % of white and asian american students earned scores of three or higher on the five-point AP interrogation scale, qualifying them for credit rating or advance course placement at most colleges. Far lower proportions of american english Indian and Alaskan Native, Black, and hispanic students earned qualifying scores ( see Figure 2 ). This entails not fair an educational disappointment but besides a fiscal shock, since these students miss out on the casual to accumulate college credits and reduce their overall tuition costs ( Smith, Hurwitz, & Avery, 2017 ) .

These disparities in AP examination scores can be attributed to a number of factors, none more important than the differing quality of the education students receive long before they ever take an AP class. not to be overlooked, though, is the education used in AP courses themselves ( Kolluri, 2018 ). typically, AP teachers trust on a lecture format because they believe this to be the most efficient way to cover a big amount of fabric ( Parker et al., 2013 ). And some students boom under that model, particularly if they ’ ve already enjoy years of high-quality teaching, including many opportunities to solve the kinds of problems and work with the kinds of material that AP exams feature. But for many other students, a lecture-based AP class entails merely another miss opportunity to engage with naturally content in sophisticated ways — such as by participating in oral presentations, debates, simulations, team-based problem-solving, and extended writing assignments — and develop the skills needed to participate in civic life and succeed in college and the work force. As one student interviewed for our sketch recounted, AP course means “ sitting in a classify and taking notes, and then I don ’ thymine understand those notes, and then fail the test and thus on. ”

Another way to teach AP courses

Given concerns about the limitations of typical AP instruction, we designed a inquiry survey to improve understanding of whether AP classes that trust on a project-based memorize ( PBL ) approach ( featuring more clock time in active, engaging coursework, and less time spent listening to lectures and taking practice tests ) can help develop students ’ deep eruditeness of subject and skills while preparing them to do well on their AP examination. We were specially bang-up to learn whether this exemplar can be effective in districts serving primarily students from lower-income households who may not have had the same tied of readiness for the course as students from higher-income households. far, we aimed to compare teachers ’ and students ’ experiences, equally well as students ’ performance on AP tests, in PBL-based versus lecture-based AP classes. frankincense, we conducted a “ gold standard ” research study, in which we randomly assigned schools to a treatment group that used the PBL course of study or a control group that did not .

specifically, we studied the Knowledge in Action ( KIA ) program, a PBL-based set about to AP that University of Washington researchers developed in the 2000s in partnership with local teachers. Our research focused on KIA ’ s AP U.S. Government ( APGOV ) and AP Environmental Science courses ( APES ), which were the first courses developed, although there is now a KIA AP Physics course a well. Curriculum and instructional materials for all three courses ( including resources such as documentation of KIA path conjunction with AP course of study frameworks and lesson plans ) are available loose through the Sprocket on-line course of study portal developed and hosted by Lucas Education Research. besides, teachers of the KIA courses in the study received ongoing, job-embedded professional memorize ( provided by the nonprofit organization PBLWorks ), including a four-day summer institute, four full-day activities during the class, and on-demand virtual coaching .

If AP teachers implement a PBL overture, they should feel confident that their students will be sufficiently prepared for the high-stakes end-of-year AP examination .

All five districts in our study were boastfully and predominantly urban. A majority of students in four of the districts were Black and/or Hispanic, and a majority of the students in three of the districts came from lower-income households ( i.e., were eligible for dislodge or reduced-price lunch ). Overall, about half ( 47 % ) of the students in our learn were Black or Hispanic and about half ( 43 % ) were from low-income households ; 38 % of exam-takers in our study were from lower-income households, compared to approximately 30 % of the national cross-course sample ( College Board, 2019 ). In summation, a goodly proportion of students in our study scored lower than average on the PSAT. Finally, all five districts had an afford AP course registration policy, meaning students did not have to meet certain prerequisites or have teacher permission to enroll in the AP run .

Our study of the Knowledge in Action program resulted in four main takeaways :

- The pattern of AP exam results was positive, both overall and for student subgroups. KIA students performed significantly better on AP exams than non-KIA students, with a greater estimated probability of earning a qualifying score on their APGOV or APES exam compared to non-KIA students (with some caveats we describe in our full research report; Saavedra et al., 2021). Notably, improved performance after one year was not driven by any one particular subgroup. Rather, we observed improved performance among KIA students from lower- and higher-income households, among students in districts serving a majority of lower- and higher-income students, in both APGOV and APES courses, and in every one of the five districts participating in our study.

- Project-based learning was a big shift for students and teachers. Teachers reported that using student-centered methods required a significant shift in their practice, and students reported discomfort with the movement away from a lecture format. For teachers, facilitating group work and pacing the curriculum scope and sequence through the year were particularly challenging. Students did not feel prepared to drive their own learning and sometimes wanted more lecture as a way to “rest” between projects. Despite the challenges, 96% of teachers who participated in the KIA program and responded to the year-end survey — even those who struggled — recommended the approach.

- Acclimating to the new approach was hard, but benefits were realized during the first year. It is notable that teachers did not need multiple years of PBL practice before we observed student successes. Our research suggests that the ongoing and job-embedded nature of the professional learning in the first year was a likely contributor to this early success. Further, we saw no erosion of the KIA model’s impact on student AP performance in teachers’ second year, after the formal professional learning had concluded (though some teachers continued to support each other through networks established in their first year). This leads us to conclude not only that participation in the yearlong formal professional learning program quickly translated to gains in AP test scores, but also that the professional learning had lasting effects on teachers’ practice.

- Project-based learning can provide sufficient preparation for AP exams. Our study is the first to provide solid evidence that if AP teachers implement a PBL approach (taking advantage of a course-specific PBL curriculum, instructional materials, and professional learning support), they should feel confident that their students will be sufficiently prepared for the high-stakes end-of-year AP exam. Nothing is lost by giving students more opportunities to work productively in groups, participate in classroom debates, provide feedback to peers, learn time-management skills, practice leadership, and refine their verbal and written communication skills. To the contrary, KIA students’ AP scores were better than those of peers who took lecture-based courses, and their teachers reported that they were more engaged in class and had more opportunities to develop real-world skills. Moreover, students tended to recognize the differences between the PBL approach and lecture-based AP classes and to report that there were significant benefits to KIA’s hands-on assignments, group work, emphasis on civic engagement, and overall approach to preparing for AP exams.

We think it ’ second significant to reiterate, though, that all of the teachers in our study who used the PBL approach had access to ongoing, job-embedded professional determine and a community of peers teaching the lapp courses. Given that PBL entails a major shift in teaching, these supports are likely to be no less built-in to its success than the course of study and materials used. indeed, based on our study results, PBLWorks, in partnership with the College Board, has begun to offer such professional learn opportunities and supports for APGOV and APES teachers. In summer 2021, they offered both a standard and PBL-based interpretation of AP teacher education. initial enrollments exceeded expectations, so we expect more courses will be available in the future .

AP, PBL, and equity

We ’ ve heard educators and policy makers say that students who ’ ve been underserved throughout their clock in school are not probably to be successful in classrooms that feature of speech active and autonomous learning. First, such students need to shore up their basic skills and acquire more content cognition, they argue, and only then will they be ready for student-driven instructional approaches like KIA .

even if educators and policy makers reject such dogmatic assumptions, they may have reservations about using non-lecture-based approaches in such a high-stakes context as AP. As one of the teachers in our study explained :

A lot of teachers have a hard time wrapping their minds around, well, my students are different than your students. Your kids have these discussions and they read, and they ’ ra prepared, and then my kids might not have anywhere to sleep tonight. Or they may not have any food on the table .

This teacher emphasized the importance of learning whether students, “ can work through project-based memorize and get the skills that they need to go on to college. ”

Our KIA results, however, challenge the impression that underserved students aren ’ metric ton ready for student-driven instruction, or that “ my kids are different from your kids ” and won ’ metric ton benefit from such an approach. The positive AP mark results we observed were not concentrated only among students from higher-income households or from districts serving primarily students from higher-income households. Rather, KIA students outperformed non-KIA students overall, and KIA students from low-income households outperformed non-KIA students from like households. In short, our results suggest that a PBL set about to teaching AP Environmental Science and AP U.S. Government can better prepare students of all backgrounds for their exams. For teachers who are already interest in shifting their practice toward PBL, this survey shows they have adept reasons to do sol. And for those teachers who have reservations, this survey suggests that it ’ s time to put those reservations aside .

Note: We have retained the condition Hispanic, since that ’ s the term used in College Board datum, and it has a slenderly different meaning from Latinx .

References

College Board. ( 2020 ). AP program engagement and performance data [ Data place ]. Author. Retrieved from hypertext transfer protocol : //research.collegeboard.org/programs/ap/data/archived/ap-2019

Read more: Jake Weary Biography from ‘TheFamousPeople’

College Board. ( 2019, February 6 ). scholar participation and performance in Advanced Placement ascend in bicycle-built-for-two. College Board Newsroom .

Finn, C. & Scanlan, A. ( 2019 ). Learning in the fast lane : The past, salute, and future of Advanced Placement. Princeton University Press .

Kolluri, S. ( 2018 ). advance placement : The dual challenge of equal access and potency. Review of Educational Research, 88 ( 5 ), 671-711 .

National Research Council. ( 2002 ). Learning and sympathy : Improving advanced discipline of mathematics and skill in U.S. high schools. National Academy Press .

Parker, W., Lo, J., Yeo, A.J., Valencia, S., Nguyen, D., Abbott, R., & Vye, M. ( 2013 ). Beyond breadth-speed-test : Toward deeper knowing and employment in an Advanced Placement course. american Educational Research Journal, 50 ( 6 ), 1424-1459 .

Sadler, P.M., Sonnert, G., Tai, R.H., & Klopfenstein, K. ( 2010 ). AP : A critical examen of the Advanced Placement program. Harvard Education Press .

Saavedra, A.R., Liu, Y., Haderlein, S.K., Rapaport, A., Garland, M., Hoepfner, D., Morgan, K.L., & Hu, A. ( 2021 ). Knowledge in Action efficacy learn over two years. University of Southern California Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research .

Smith, J., Hurwitz, M., & Avery, C. ( 2017 ). Giving college credit where it is due : promote Placement examination scores and college outcomes. Journal of Labor Economics. 35 ( 1 ) .

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Kappan, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp. 34-38 .

ANNA ROSEFSKY SAAVEDRA ( asaavedr @ usc.edu ; @ AnnaSaavedra19 ) is a research scientist at the Domslife Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. AMIE RAPAPORT ( arapaport @ gibsonconsult.com ) is film director of research at Gibson Consulting Group, Austin, TX. KARI LOCK MORGAN ( klm47 @ psu.edu ) is an assistant professor of statistics at Penn State University, University Park, PA. MARSHALL W. GARLAND ( mgarland @ gibsonconsult.com ; @ mwgarland ) is a senior research scientist at Gibson Consulting Group, Austin, TX. YING LIU ( liu.ying @ usc.edu ) is a research scientist at the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

ALYSSA HU ( awh70 @ psu.edu ) is a ph candidate in statistics at Penn State University, University Park, PA. DANIAL HOEPFNER ( dhoepfner @ gibsonconsult.com ) is a research scientist at Gibson Consulting Group, Austin, TX. SHIRA KORN HADERLEIN ( Shaderlein @ mathematica-mpr.com ; @ Shira_Korn ) is a research worker at Mathematica Policy Institute, Princeton, NJ .